Back in the last century and through the early 1900’s researchers operated under the assumption that intelligence was a uni-dimensional construct. You were either smart, or you weren’t. And how smart you were could be measured with one test resulting in one number: IQ.

Back in the last century and through the early 1900’s researchers operated under the assumption that intelligence was a uni-dimensional construct. You were either smart, or you weren’t. And how smart you were could be measured with one test resulting in one number: IQ.

In the 1970’s a shift began away from the IQ construct. Gardener argued in his Theory of Multiple Intelligences that there were up to ten kinds of ability: musical-rhythmic, visual-spatial, verbal-linguistic, logical-mathematical, bodily-kinesthetic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, naturalistic, existential, and moral. Sternberg proposed practical, creative, and analytical intelligences. Daniel Goleman popularized the notion of emotional intelligence, or EQ. While these theories add considerably to our understanding of broader abilities and what it takes to be a happy and successful person, I’d like to focus in this blog on the kinds of mental abilities required to reason, solve problems, think abstractly, and comprehend complex ideas. What I’d call “intellectual abilities.”

Research has advanced to the point where we probably know more about the underlying cognitive and brain processes involved in mental abilities and intelligence than any other complex psychological construct. Click here for more information on this concept. The consensus is that the most useful and descriptive model of intelligences is the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) Model. This model has become so prevalent that nearly all modern IQ tests have been changed to incorporate the theory as their foundation.

I find the CHC model to be a very useful framework for understanding individual student’s ability profiles and how they impact learning –how they are intelligent.

The CHC model identifies over 80 different cognitive abilities. About 30-40 of these are important in school learning and achievement. The others, like “musical discrimination and judgment,” aren’t as directly related to academic achievement.

It is a fact that most of us have uneven profiles of strengths and weaknesses across these 30-40 abilities. Let me illustrate the concept. But instead of showing all 30-40 school-related abilities, I’ll illustrate the point with 11 of the more important ones (e.g. verbal reasoning, listening ability, inductive and deductive reasoning, aspects of memory, processing speed).

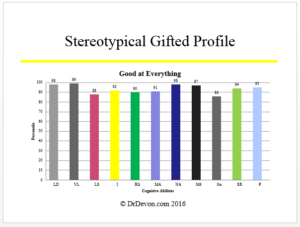

The stereotype of a highly intelligent, gifted child is that they are good at everything. If they were, one would expect to see a profile like the graph below – all abilities would be in the highest ranges.

I rarely see a uniform profile like this, even among highly and profoundly gifted learners. Most gifted students are not equally gifted at everything. They may have some abilities in the average range and even some in the well below-average ranges.

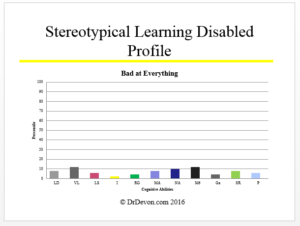

The flip side of the gifted stereotype is the learning disabled stereotype. This stereotype holds that students with learning disabilities are bad at everything academic/intellectual. A student who is weak in all of the cognitive ability areas contributing to academic learning would be expected to have a flat profile with low scores in all areas.

I have never seen a student with learning disabilities with a flat profile like this. Students with learning disabilities, by definition, have areas of cognitive strength. They are not bad at everything. But when I ask students who are having difficulty at school what they think their profile looks like, many think it looks like the graph above. They’ve lost sight of their strengths (if they ever knew they had them). They tend to think they’re "bad at school” and maybe even “not too smart.”

In reality, very few people are good at everything or bad at everything. Most of us have uneven profiles with strengths in some areas and weaknesses in others – more like the chart below. Terms like “gifted” and “learning disabled” are too vague to describe these variations. Gifted at what ability? How gifted in that specific ability area? Learning disabled at what? How learning disabled in that specific ability area?

From a practical standpoint what’s important is to understand where the student's strengths and weaknesses are, and how to work with them. How they're intelligent.

Recently I worked with a boy whose parents and teachers felt he was not achieving his potential in school, and wondered if he might have ADHD or a learning disability. Zack was a hard-working and motivated student who was engaged in class, diligently turned in his homework, and studied hard for tests. He tended to get great marks during the semester but couldn’t seem to break a “C” on tests and exams. My assessment ascertained that he didn’t have ADHD or a learning disability, and he had a nice solid IQ at the 90th percentile. But he had a surprising weakness in long-term auditory memory. This explained his underperformance – he wasn’t consolidating learning efficiently into long-term memory so he couldn't efficiently retrieve what he had learned for tests and exams. The good news for Zack and his family was that this is quite fixable. One can get better at memorizing and storing information. We came up with a tutoring plan to build his ability utilizing his stronger visual memory and fluid reasoning.

An understanding of how the student is intelligent can be helpful to any child (like Zack, who it turned out was neither learning disabled nor gifted, but had an area of weakness that needed to be addressed). But it is especially important for twice-exceptional learners. The discrepancies between the twice-exceptional student's strengths and weaknesses are more extreme than they are for most people. This unevenness of abilities causes considerable frustration. A 2E student may have very strong vocabulary and verbal reasoning, and excellent listening ability and fluid reasoning (inductive and deductive thinking), but their weaknesses in ability areas like phonetic coding and naming speed may severely inhibit their ability to read and demonstrate what they know in writing. In other words, they may be dyslexic. Or they may have extremely high quantitative reasoning and visual spatial ability yet be unable to reliably process information quickly and efficiently due to slow processing speed. An in-depth assessment of cognitive strengths and weaknesses is a very important step in figuring out how to help such students achieve their considerable potential.