Multi-potentiality is the state of having many exceptionally strong abilities or talents. The child who has the Midas touch and is good at everything he does from math to science to English to music to sports to art to leadership has multi-potentiality. It sounds wonderful doesn’t it? But for many children and young adults it can becomes a burden.

Why?

External Reasons: If you’re good at something, people tend to encourage you to pursue it. The child who is good at a lot of things may be pulled in many different directions by well-meaning teachers, coaches, and parents. Who should the child listen to? Their violin teacher who’s urging them to apply to Juilliard, their math teacher who wants to enter them into prestigious math competitions, or their tennis coach who’s encouraging them to become a nationally ranked player? There simply isn’t enough time in the day to pursue all of these talents. Disappointed adults can make the child feel he is “wasting his potential” if he doesn’t follow their advice and encouragement. This is particularly difficult when a parent has a dream for their child that fits with one of their child’s strengths. How can they let their parent down by not pursuing it? It’s a lot of pressure for a child to feel they need to live up to another’s expectations and dreams.

Internal reasons: We often decide what we’re interested in and want to pursue based on our abilities. The multi-talented high school student may try to do everything they’re good at and become so over-scheduled and exhausted that they have little time for reflection (or sleep). Adolescents and young adults approaching critical decision points like what major to declare in college and what career to pursue afterward may experience debilitating anxiety and stress over the decision. The student who excels at math and science but just gets by in English may decide to lead with his strengths and major in a STEM field in college. But the student who is good at everything may feel overwhelmed by the multitude of choices before him. I had a gifted friend in college who was brilliant at everything. She still hadn’t decided what to do in our senior year so she sat for the LSAT, GRE, and GMAT, thinking she’d choose between law, business, and graduate school based on her test scores. Her scores came in at the 99th percentile on all three exams, leaving her no further ahead in her decision-making.

What can we do to help students suffering from the downsides of multi-potentiality?

First, it’s important to encourage the child to try to not be influenced by external influences. They shouldn’t feel pressured by others to use their gifts. Parent alert: just because you wanted to be a concert pianist and your child appears to have the talent to do so doesn’t mean you should live your live through theirs.

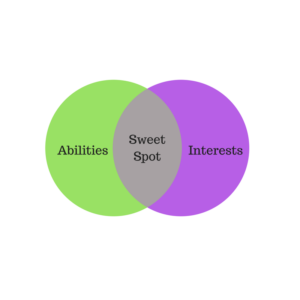

Second, it’s important to inculcate the importance of genuine interests as a driver from a young age. Abilities are one thing – they are what the student is naturally good at. Interests are another thing altogether. Interests are what the child is drawn to. A child can be good at something they aren’t that interested in and interested in something they aren’t that good at. A way of helping the multi-talented child narrow his or her list of possibilities is to focus attention on what genuinely “lights their fire.” Interests can be formally assessed, but there are also ways parents can flush them out. Ask yourself: What makes my child smile and laugh? What gets and keeps my child’s attention? What gets my child excited? What are my child’s favorite things to do? What is my child willing to work hardest at doing? What “brings out the best” in my child? And what does my child choose to do most often in his or her free time (assuming they have any)? For most children, identifying these genuine interests significantly narrows the list of possibilities. A “sweet spot” can often be found where abilities and interests intersect, but I feel interests should win any contest between the two. The gifted child with multiple abilities is likely to be able to develop stronger abilities with effort in an area of strong interest.

Of course there are some children with multi-potentiality who are interested in everything too. For these children I recommend the Chinese menu approach. Take one interest from column A (academic subject), one from column B (arts activity), and one from column C (physical activity). Explore these for some time. Then try other items. This can be an iterative process until about high school when I feel it is best to narrow one’s commitments to at most 3-4 major areas.

Adding values to the mix can further narrow the list. Values are intrinsic core “wants” - the deep inner reasons or desires that motivate us like money, status, autonomy, fame, helping others, variety, power, security, risk-taking, and changing the world. The multi-ability, multi-interest child may be able to focus their efforts further if they consider what they truly value. This requires honest reflection.

It’s also important to let children know that the average person changes careers 3 to 7 times in their lifetime. They may be able to be a scientist and a doctor and a musician and an artist and an environmental activist in succession. Or they may successfully combine several disciplines into one career. While it’s harder today to be a polymath like Leonardo da Vinci, examples can be found of people who successfully combine fields. Noam Chomsky combines cognitive science, philosophy, psychology, and linguistics. Stephen Wolfram is a computer scientist, mathematician, physicist and cosmologist. Viggo Mortensen (perhaps best-known as Aragorn in The Lord of the Rings) is a professional singer, composer, photographer, painter, founded a publishing house, and publishes poetry he’s written in three languages.

Another idea is to let children know that they can pursue their extra interests outside of their careers as hobbies. They can sing in the local choral group, coach baseball, and even build a lab in their garage to tinker with tech start-up ideas. All while having a full-time job doing something else.

No child is really “too gifted.” They just need to figure out which gifts among an abundance of many to open and play with first. If you would like to learn more about how to help your gifted child, contact Devon MacEachron, PhD.

This blog article is part of the Hoagies' Gifted Education Blog Hop on “Multipotentiality.” I thank my friends at Hoagies’ Gifted Education Page and elsewhere for their inspiration, support, and suggestions.