I was asked to write an article on this topic for TECA (Twice Exceptional Children's Advocacy), an online community providing service and program directories and information about advocacy. I decided to enlist the help of Benjamin Meyer, a therapist specializing in young adults with NVLD and Asperger's in the workforce. Here's what we wrote:

By Benjamin Meyer, LCSW and Dr. Devon MacEachron, PhD

You did it! Your child has finally received an acceptance letter to a college or university and is beginning his or her first steps toward adult life. All your hard work navigating the treacherous path of diagnosis, remediation, social skills training, OT, PT, gifted programming, IEP’s and 504’s has paid off. You deserve a lot of credit for all that you have done to guide your child through the process, and you certainly deserve to celebrate!

While high school has come to an end, it is important to keep in mind that even after college, your child may face challenges related to their disabilities. These can include identifying and finding a career they enjoy, adapting to the world of employment, making friends with peers, and adult dating. Many young adults with learning differences are unemployed or underemployed due to the more nuanced social and executive functioning demands of the workplace, The National Center for Learning Disabilities reports that only 46 percent of work-age adults with an LD are employed (Cortiella, 2014) . “Failure to launch” has become a national epidemic, with many young people returning home to live with their parents due to challenges with the professional and social demands of adulthood. Your high school grad will be at an advantage if they take a few practical steps while in college to prepare for the “real world”.

Young adults in our practices often identify specific challenges at work related to their learning profiles. The dyslexic who chose engineering or architecture due to his gifted visual-spatial skills may find that slow speed and miscalculations made in math problems hinders his ability to complete tasks efficiently. The ingenious marketing professional with ADHD may experience difficulty organizing her ideas into action plans. The gifted writer with Asperger’s Syndrome or NVLD may struggle to hold regular employment due to difficulties reading their peers’ body language. Young adults who plan in advance for a career or job that will be a good fit for their unique profiles are most likely to be successful transitioning to the world of work.

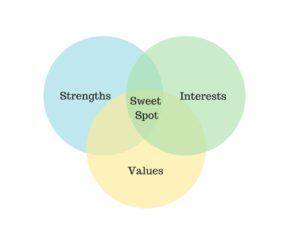

Finding the Sweet Spot

When deciding on a career, young adults can search for the “sweet spot” where their strengths, interests, and values coincide (see diagram). The blue circle represents strengths. These should include intellectual talents as well as people skills, executive function, willingness to work hard, artistic, musical, and any other abilities. The green circle encompasses interests: sports, outdoor activities, academic subjects – any and all interests the individual may have. Lastly, it is important to identify and “own” the personal values that can impact career satisfaction. These include: how important a flexible work schedule is, how much social interaction is desired at work, the hours one is willing to work, desire for autonomy and independence versus taking direction from a boss, whether one enjoys working on a team, being outdoors versus in an office building, how important a high salary is, how important it is have a high prestige position, whether one wants to be considered an expert or authority, how important it is to feel one is helping others or making the world a better place. Values go in the yellow circle. By identifying the key factors that influence career success and happiness, young adults can begin to see which careers might fall within their “sweet spot.”

Acknowledging and Factoring in Areas of Challenge

While students are searching for their “sweet spot,” they will also benefit from being honest with themselves about their challenges. There are certain skills that are important in practically any job. Relating to colleagues, keeping your emotions in check, taking initiative, and having an organizational system are a few of them. There are also specific skills required in different fields, e.g. math skills for an actuary or writing skills for a journalist. If the student feels they have a weakness in an area important to a career they feel they would like to pursue, they can work on developing those skills while still in college. For example, they might learn to create an organizational system with a coach or work with a therapist on professional social skills. The student will also benefit from consulting with professionals who are in the field they are considering, especially those who have a similar profile of strengths and weaknesses. This will help them assess how suited their specific strengths and weaknesses are with the demands of the job and will aid in identifying some strategies for compensating for their weaknesses. Internships and mentorships are ideal opportunities to practice compensation strategies while building on strengths, experience and expertise.

Case Studies

Jacob is a verbally gifted 2e student with nonverbal learning disability interested in becoming a social worker. He realizes that he may find meeting documentation requirements challenging due to executive functioning deficits, while also facing obstacles reading nuances in body language from colleagues and employers. On the other hand, his strengths in writing and verbal skills will help him to produce well-written progress notes and describe cases in detail. As is the case for any 2e student, expressing specific strengths to potential employers during and after the interview process is a critical skill for landing a good job. Twice-exceptional students have exceptional strengths and these can be a major attraction to employers. But prospective employers may not know what those are until the applicant articulates them in a clear and concise way, convincing the employer of their value. Jacob needs to sell his verbal and writing skills. At the same time, he should anticipate concerns about weaknesses and consider addressing them up front. If a prospective employer knows that Jacob has NVLD and what NVLD means, they might be concerned about Jacob’s organizational abilities. Jacob would be wise to highlight in the interview process that he worked on developing a unique filing system at his last job, and explain how this skill will help him be an effective social worker.

Neil is a brilliant mathematician and visual-spatial thinker with Asperger’s and ADHD. He struggled with attention and making friends in college, however he successfully identified a strong interest and talent in architecture. Neil knows that he will no longer have access to a note taker, extra-time on tests, and academic coaches to help him stay on task in the work world. Also, an understanding of business social skills will be critical for him to engage effectively with clients in this field. During his last two years of college, Neil decided to work with a therapist building business-savvy social skills. During the summer when he is interning at an architecture firm he intends to consult with a business organizational coach and mentor who understands some of the demands he is likely to face in an architecture career. When Neil interviews for full-time jobs after college he may request “reasonable accommodations” that will not create an excessive burden for the employer. These could include extra filing space, access to a computerized organizational system, and a co-worker to accompany Neil to organizational meetings and provide professional feedback, etc.

Caroline is a 2e student who is dyslexic and has ADHD. She wants to be a journalist. She hit some road-bumps along the way in college from her ADHD and as a result it took her 6 years to graduate. She’s decided she needs to address this up-front in her interviews by explaining that she has ADHD, what happened, and what she learned from it (e.g. how to be organized, how much she cares about learning). When she mentions her ADHD she intends to emphasize that she thinks it is part of the reason she is so creative as a journalist and point to examples of creative stories she has published. But she doesn’t think her dyslexia will negatively impact her future work because she knows to get her pieces edited for spelling and grammatical errors. So she’s not planning on mentioning that exceptionality.

Does Your 2e Learner Have to “Tell All?”

It depends. In an ideal, open-minded, accepting-of-neurodiversity world one would be up-front about such things. No one wants to end up in a position that’s a bad fit. On the other hand, although they legally cannot discriminate, prospective employers may be concerned about hiring someone who brings challenges along with them. Many people don’t know about twice-exceptionality and may not get that one can be gifted and have a disability. We recommend the student decide in advance how much information would be in their best interests to divulge. The decision of what to share may be influenced by how overt the student’s weaknesses are. If you can’t hide it, own it. The decision may be influenced by the culture in the specific career field or company. Technology firms and academia tend to be more open-minded to differently-wired people. Traditional businesses like manufacturing and law may be less so. Of course if the student does decide to share, thought should be given to how to frame such information in the most informative light.

When a 2e student is proactive in preparing for future employment during the college years, their chances of success are greatly improved. These steps can include: researching and selecting a career that fits well with their unique profile of strengths, challenges, and values; working to address organizational and “soft skills” deficits while still in college; and finally deciding what and how much to self-disclose. Although 2e young adults may face challenges adapting to the workforce, they can be proactive about creating strategies for overcoming these boundaries, especially if they start doing so during the college years.

Benjamin Meyer, LCSW is a bilingual psychotherapist who provides psychotherapy and coaching services to young adults with High-Functioning Autism and Nonverbal Learning Disorder post-college in New York City. Dr. Devon MacEachron, PhD is a psychologist with expertise in twice-exceptional learners who provides psychological assessment and educational planning services to children, young adults, and their families in New York City.

Works Cited

Cortiella, C. &. (2014). The State of Learning Disabilities: Facts Trends and Emerging Issues . New York, NY : The National Center for Learning Disabilities.